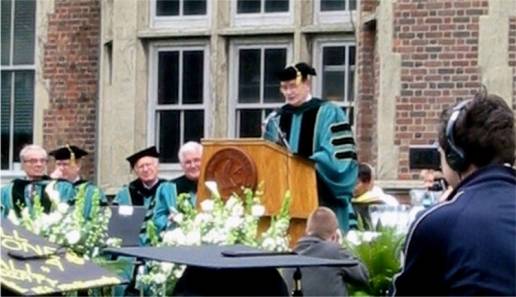

Arthur O. Anderson M.D. [B.S. Biology '66]

Wagner

College Honorary Doctorate 16 May 2003

Fellow Graduates

and Honorees, United States Senator Schumer, NY State Senator Marchi, Members of the Board of Trustees, President and Mrs. Guarasci, Chaplain Guttu, Members

of the Faculty, Ladies and Gentlemen, I am deeply honored to join you, the

class of 2003, as you mark this milestone in your lives, and commence on paths

that will take you into the world and define your place in it.

As you conclude

your years as students of Wagner College, your time spent here will remain as

significant throughout your lives as it is today; and as it remains for me

thirty seven years after graduation from Wagner.

Thank you for bestowing on me this honor. I am not a

celebrity, a prizewinner or a doer of conspicuous deeds. My lifetime achievement, which you have just

heard described, can be traced to beginnings at Wagner. I received the best moral education to

prepare me for medical school, scientific research and responsibilities in applied ethics, culminating in my present position as Chief of the Office of Human Use and Ethics at the Army’s Biological Warfare Defense Laboratory.

My Biology professor, Dr. Ralph E Deal also provided moral

education in his Histology course. One of the lessons he taught was that some anatomic structures described in the textbooks are not always present. During practical exams each tissue structure

correctly identified earned one point. Two points were subtracted if we claimed to be able to see a structure that the textbook told us should be there, but was intentionally not included in the sample for the exam. This lesson emphasized observational

integrity that became important to my future in research. It also required

moral courage to say you did not see what your text or scientific authorities

said should be seen.

Wagner’s liberal arts curriculum enabled me to accomplish my

educational goals and encouraged me to broaden my vision. I enrolled in

required courses offered in the Religion and Philosophy department. It amazed

me how studying philosophy liberated me from the dogmas at home, freed me of my

own prejudices and gave me tools I could use for making ethical decisions.

My education continued outside the classroom through

conversations with my friend and classmate Fred Sickert. We often bounced issues

off each other to see how they squared with the precepts of different

philosophies.

And, I participated in “Faith and Life Week”, a campus-wide

symposium on ethical decision-making, where participants analyzed the

relationships of Intentions to Actions, and of Actions to

their Consequences. Careful analysis of the alternatives can identify

actions that yield remarkably different results, results that can produce

success with less negative consequences if you make the right choices.

At the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Ethics was

not a part of medical curriculum in the 1960s so I found that raising ethical

questions was challenging to my professors, but my asking did no harm.

During Pathology training at Johns Hopkins, I also raised concerns

about patients who had come to autopsy after failing fruitless long-term

treatments that forced them to live out their final days in the hospital.

Today, medical students are taught ethics, hospitals have

ethics committees to assist families in making just and ethical choices about

end of life decisions but failures of research ethics still appear on the front

page.

As my postdoctoral training at Johns Hopkins was nearing

completion, my basic research in immunology was taking off. I had made several new discoveries related to how the cells of the immune system move around the body and I wanted to continue with this research. I had a prior obligation to go on active duty in the Army as soon as I completed my training so taking a faculty position had to wait.

The US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious

Diseases at Fort Detrick was a place where I could serve my obligation and also

continue doing research. Some of you may recognize the acronym USAMRIID (pronounced Use Am Rid), it has been in the news, novels and movies after

publication of the Hot Zone, by Richard Preston. The institute develops

diagnostics, drugs and vaccines to defend against biowarfare; and, more

recently, bioterrorism.

USAMRIID has a research program where human subjects serve

as volunteers in protocols to test safety and utility of vaccines and

drugs. In 1975 I heard some details

about a study involving human volunteers that I thought was too risky for the

value of the information that might be learned. I mustered the moral courage to march into the commander’s office

and inform him

that I thought it would be a terrible mistake to do that study.

Rather than being shown the door, the commander respectfully

considered my concerns and put the study on hold. The next time I spoke with

him he appointed me the first chair of the “USAMRIID Human Use Committee”. It would be my committee’s responsibility to

decide whether or not protocols should be approved and carried out. I had been given a huge responsibility that

had predictably huge consequences.

Over the 28 years that I held this responsibility, there

have been no deaths or injuries and our Project Whitecoat volunteers speak affirmatively about

the respectful and ethical environment in which these studies were carried out.

It didn’t occur to me right away that the decisions I made, leading to our

stellar record for protecting the rights, safety and welfare of volunteer

subjects, had their origins at Wagner College. The required philosophy courses

were valuable credentials that served as my unseen partner in all these

efforts.

In accepting this honorary degree – I wish to tell you – how

lucky I was to be a student at Wagner, to be liberated by my education to think

independently and to have been given such a good start in life.

I wish all of you the most success. I am confident that in

years to come you will be able to return to Wagner College and tell similar

stories of success, moral courage and ethical behavior as you move on into your

future.